Mistakes can be costly, but they can also be a valuable way to learn. Tom Vaughan asks 10 industry leaders what their biggest mistakes have been and what they took from the experience.

The wrong concept: Des Gunewardena, chief executive, D&D London

"When we opened our restaurant Alcazar in Paris, back in 1998 – in our Conran days – there was a long-disused site of a famous nightclub called Whisky A Go Go. This was the inspiration for the even more famous Los Angeles version. Many of the big rockstars played there when in Paris – the club was perhaps best known as where Jim Morrison of the Doors performed the night before he took his own life.

"We thought it would be great to reopen the club as the home of British house music in Paris, so we did a deal with London's Fabric guys to launch and run it for us.

"We were rammed, but our revenues were rubbish. We hadn't figured out that while Fabric in London was full of high-spending City boys and girls, the house music scene was very different in Paris. Over there our club was packed with kids from the suburbs who arrived at the club already ‘jolly' and just drank mineral water all night.

"We changed the concept to ‘Car Wash'. Not as cool, but it paid the bills. The lesson for me? It's fun to do different things. But if you want to make a profit, it's best to stick to what you know."

It's fun to do different things. But if you want to make a profit, best to stick to what you know

The dodgy lease: Will Beckett, co-founder, Hawksmoor

"Probably our single biggest mistake was signing the first Hawksmoor lease. We had no money, and we trusted a bank's word that they would provide a loan (they didn't). Huw [Gott]'s parents ended up remortgaging their home to help.

"It turned out the restaurant didn't have planning permission to be a restaurant, and we had added a fourth business to an ‘empire' that was already crumbling around our ears. We couldn't cope and we almost went bankrupt. It is single-handedly the absolute worst decision we've ever made, and yet neither of us would go back and change it for a moment.

It is single-handedly the absolute worst decision we've ever made, and yet neither of us would go back and change it for a moment

"There are almost as many ways to be successful in restaurants as there are successful restaurants, but so many failures come from a small number of often-repeated mistakes. Huw and I have made most of them – in fact, it's probably fair to say that we've made as many bad decisions as good ones. We've opened 16 sites: eight have succeeded and eight have failed. We've just been lucky that all the successes have been Hawksmoors, whereas anything else we've tried has failed."

The muddled press campaign: Linda Lee, founder, On the Bab and Koba

"A few years ago, I opened a concept store in Soho called Mee Market. To me it was very clear what it was – a store selling a carefully chosen selection of Korean food, stationery and homeware, alongside a counter serving Korean street food, different from that served at On The Bab. It was neither a restaurant nor a shop – a concept very popular in my home city of Seoul.

"However, for press and the public, Mee Market was confusing. Some people came expecting it to be much bigger, like the wonderful Japan Store. Others came thinking it would be all food – like a market – and then didn't understand why there were also magazines and notepads.

"So I learned that it is really important to communicate clearly what any new concept is so that customers know what to expect – especially if you are already well-known for a particular product or brand.

"Shortly afterwards, I opened On The Dak, a one-year pop-up specialising in Korean fried chicken, similar to what we served at On The Bab. This was instantly understood. The name (‘dak' means chicken in Korean) and visual branding were similar enough to On The Bab for people to understand that the brands were related, but different.

"So the lesson is, when launching a new brand, make sure that you communicate very clearly what it is and what you are offering."

Make sure that you communicate very clearly from the outset what a brand is and what you are offering

The lack of a financial director: Wendy Bartlett, founder, Bartlett Mitchell

"My biggest mistake in business was not getting a financial director sooner in the Bartlett Mitchell journey. I've always been a foodie at heart and finance is neither my passion nor interest. I feel we would have fared much better had I got one much earlier on. The cost would have paid for itself!

"To succeed in hospitality, food needs to be the starting point and a sharp focus for a successful company in our business. However, it's important to remember that there are other skills needed and experts should be brought in to build a more rounded team.

"When I did eventually get a grown-up in finance, I was blessed to have had two brilliant financial directors whose counsel I could fully trust. Their influence helped us achieve what we needed and allowed us to take measured risks, invest in the right things and make sure the cash flow was positive."

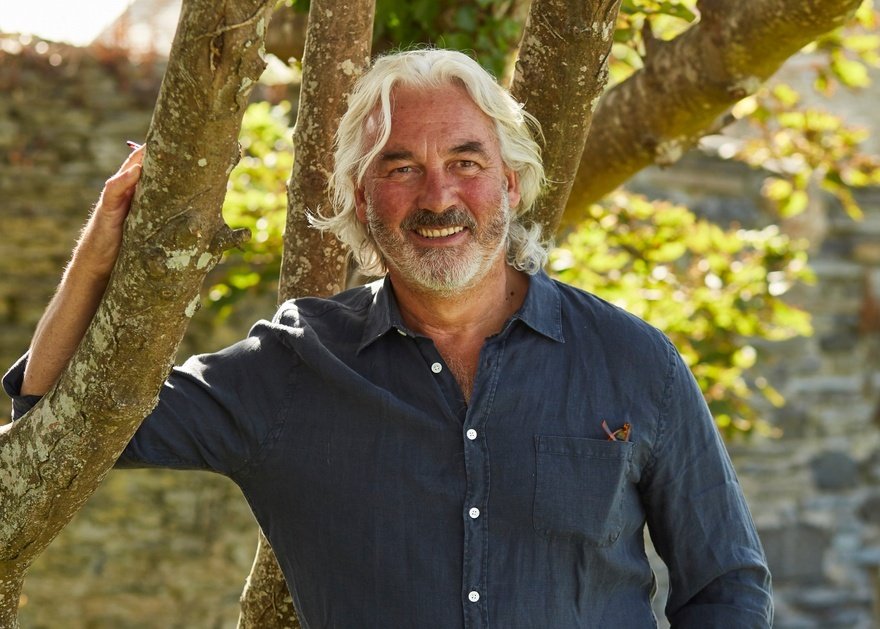

The Nigerian con artist: Robin Hutson, founder, the Pig hotels

"My bigger gaffes have usually been around a slight lack of financial caution. The one that always springs to mind was when I had my first management role as reception manager at the Berkeley in 1979. I had only been in the job a couple of weeks and I was hoodwinked by a Nigerian con artist who stayed in a suite. He kept paying small amounts on his account, gaining my trust but extending his stay. I was so green and naïve I believed his stories about how the cash would be delivered by private plane from Geneva. He hired the hotel's Rolls Royce Phantom and was swanning around London, sending charges back to the hotel – you could do that in those days.

"Eventually, he did a runner, owing the Berkeley about £10,000, which was a huge amount of money in those days. He was caught because he still had the Rolls – it was parked outside the Hilton in Park Lane. He was deported but the hotel never got the money back. I learned a big lesson."

The messy departure: Tom Aikens, chef-patron, Muse

"The exit I had from Pied à Terre [when Aikens resigned after allegedly branding a teenage member of his team with a hot knife] was a foolish mistake that I deeply regret.

"There are various reasons, which legally I can't go into, about why I did it, but it went from a kitchen incident to the 6pm news broadcasting live outside the restaurant.

"I couldn't get any work. I had difficulties in paying my mortgage. Personally, it took a lot out of me. I was at a pretty low point. I was still young – 28 or 29. I separated from Pied à Terre and pretty much lost all my money.

"Looking back, I'd have told myself to step back, focus, breathe, and then get advice – which I didn't do. I should have got other opinions from both the business side and from other people higher up in the industry. It was harder back then – people weren't as keen to help each other as they are now.

"I think of it as a lesson. I definitely learned a lesson personally. You have to take stock and change. I've always said forget about the past and move on. But the stigma is still there and it will always be on my gravestone."

The slapdash marketing campaign: Tom Barton, co-founder, Honest Burgers

"It was the run-up to opening our sixth site. We were just starting out and were spreading ourselves really thinly across the different elements of the business, and, as a result, ended up doing stuff that we weren't very good at.

"I had a very important board meeting with our new investors and I simply didn't have the time to prepare for it. I wanted to impress them with how quickly we could drive engagement, so I decided to do a very slapdash campaign offering a free burger if you signed up to our newsletter.

"Looking back now, I should have had the confidence to walk into the meeting and say: ‘I'm sorry, I've been so busy opening a restaurant that I haven't had time to prepare properly'. Instead, I was desperate to impress.

"I expected a thousand or so sign-ups. Instead, we got about 9,000. The team were already under pressure with the launch of the restaurant and I had just made everyone's life a whole lot harder. When we opened, the queue stretched down the street, most of them holding free burger vouchers. I just had to go in there with my head hung low, hold my hands up and apologise. Then I put on an apron, helped them every way I could and we worked our socks off.

"We ended up giving away about 20,000 free burgers – the vouchers were easy to replicate – which cost the company about £40,000. It was my mistake alone. My most important lesson – not just in business but in life – is don't hide behind your mistakes, own them."

Don't hide behind your mistakes, own them

The wrong career move: Emma Williams, chief operating officer, Green & Fortune

"When I left Searcys at the Royal Opera House, I was deputy general manager. I was relatively young, in my late twenties/early thirties. I left it because the bright lights shone brighter, and I had the chance to go and be GM at the Royal Albert Hall, working for Compass.

"I lasted three months and gave my notice in. Don't get me wrong, Compass has some great values and great staff, but culturally it just didn't fit for me. I only ever really succeeded in smaller companies.

"I come from a family business, and I'm used to being part of the process and part of the decision-making and seeing the output. You can't be afraid of owning up to your mistakes – of having egg on your face because you'd told everyone you were going to move. I wasn't going to suck it up for three years because I'd be miserable and wouldn't deliver for the company. So I decided I was going to be brave and step away from it.

You can't be afraid of owning up to your mistakes – of having egg on your face

"I ended up learning a lot at a smaller company, and then I joined Green & Fortune, which was much smaller at the time. It allowed me to develop the company with the owners. While the smaller companies probably don't seem to offer as big an opportunity or as big a salary, you've got to fit with the culture that suits you, the one that lets you blossom and enjoy your job."

The expensive hire: Cokey Sulkin, co-founder, Dirty Bones

"The most difficult decisions often come down to your team: do you grow your own team or go for the expensive hire with a wealth of experience?

"One of our mistakes was to go for the expensive hire and to then put a halo on them because of the ticket price. They came into the business on one of the biggest salaries we have ever paid, and then started taking the business in a direction that didn't work. It took me a year to realise that beyond the glossy terminology they weren't pulling the punches, and it was a huge expense to disentangle ourselves from that direction.

"I'm not saying always go for homegrown, but when you do go for calibre, do a deep dive around that individual. When you make a key hire like that, send them through the interview process multiple times – yes – but also get them to do a piece of work for you, so you can gauge the way they present information. How do they work? What are they going to bring to the table? What value are they going to add over and above what you've already got in the business? And don't put a halo on them."

The feeder instinct: Ravinder Bhogal, founder, Jikoni

"Every now and then I get possessed by the spirit of all the Punjabi feeders I grew up around and get into an over-feeding frenzy. It comes from a place of generosity where you just want to give your guests absolutely everything you have, but you may kill them with kindness or gout in the process.

"Last year we hosted The Times columnist Sathnam Sanghera as part of our Civilised Sundays series, where he was talking about Empireland, his upcoming book. I cooked a five-course menu, which may sound reasonable, but one of the courses was a Panjabi thali, which was made up of 13 separate dishes! Our guests all regretted not wearing trousers with elasticated waists. My feeder instinct is something I have had to learn to reign in."

I cooked a five-course menu, which may sound reasonable, but one of the courses was a Panjabi thali, which was made up of 13 separate dishes

Continue reading

You need to be a premium member to view this. Subscribe from just 99p per week.

Already subscribed? Log In